How guitarists use the B string to master standard tuning

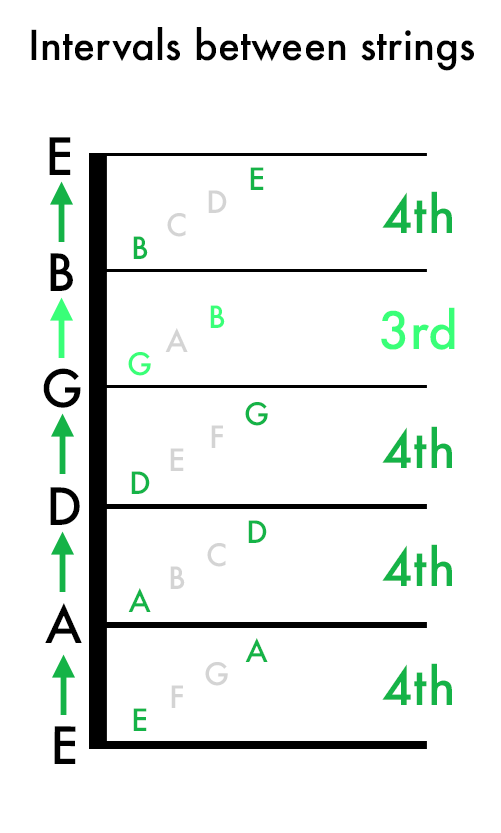

The strings on the guitar are all an interval of a perfect fourth apart. Until we get to the G string; the distance between the G and B strings is an interval of a third.

Your first thought might be something along the lines of, ‘Wouldn’t it be easier to have all the intervals the same?’

You’d think so, but it turns out that the sneaky little major third interval hidden between the G and B strings is more useful than it first might seem.

Why isn’t the guitar tuned in fifths?

Fig. 1: Intervals between the strings on the guitar.

Stringed instruments like the violin and the cello are tuned in fifths and have been around a lot longer than the guitar. So, why didn’t we end up with a modern guitar that has strings tuned in fifths? After all, we sometimes tune to Drop D and that puts the two lowest strings a fifth apart.

It actually comes down to what the different intervals allow us to do on the guitar. Drop D is great for chunky power chords but the distance of a fifth between the strings becomes problematic when we start playing scales or chords with complicated fingerings.

The interval of a fifth works on instruments like the violin or the cello because they have shorter scale lengths. However, the guitar has a much longer scale length, so having strings separated by the interval of a fourth means we have to do a lot less reaching.

We always aim to be as efficient as possible when playing the guitar. Trying to ‘do a lot less reaching’ is one of the reasons why having the G and B strings separated by a sneaky little third interval is such a great idea. Scales and chords are easier to play, our fingers are more centred, and we don’t have to change positions as often as we otherwise would.

Tuning the guitar like this makes chords sound good

Another benefit of having the random little third interval between the G and B strings is the way it allows us to play guitar chords that actually sound good!

Tuning perfectly in fourths would give us a high F string. F is only one semitone away from E and they will often sound quite dissonant when played together. If the top string was an F, we’d find we would have to spend a lot of time trying to mute notes that would make the chord sound bad if we heard them ring out together.

Having two E strings and a B string allows us to play most chords without unnecessary muting and gives us the additional benefit of being able to use these strings as ambient drone notes when we’re playing open chords in the key of E. The key of E is a favourite among guitarists - probably because of the fact that we have a sneaky little third interval which gives us a B and extra E string!

The problems with playing the guitar in standard tuning

We’ve talked about some of the benefits of having the interval of a major third between the G and B strings (when all the other strings are a perfect fourth). However, changing the distance between strings halfway down the fretboard isn’t all good. This sneaky third interval does create some complications and if we’re not careful it can be a lot more frustrating than it needs to be. We might not even realise how it might be holding us back from progressing on the guitar!

If we had the same interval between every pair of strings then our scale and chord shapes would be the same regardless of which position we played them in. Having one random major third interval part of the way down really messes this up.

At least, it does if we don’t understand how the B string behaves. Once we’ve figured this out we can avoid all the frustration and just focus on the benefits we talked about earlier.

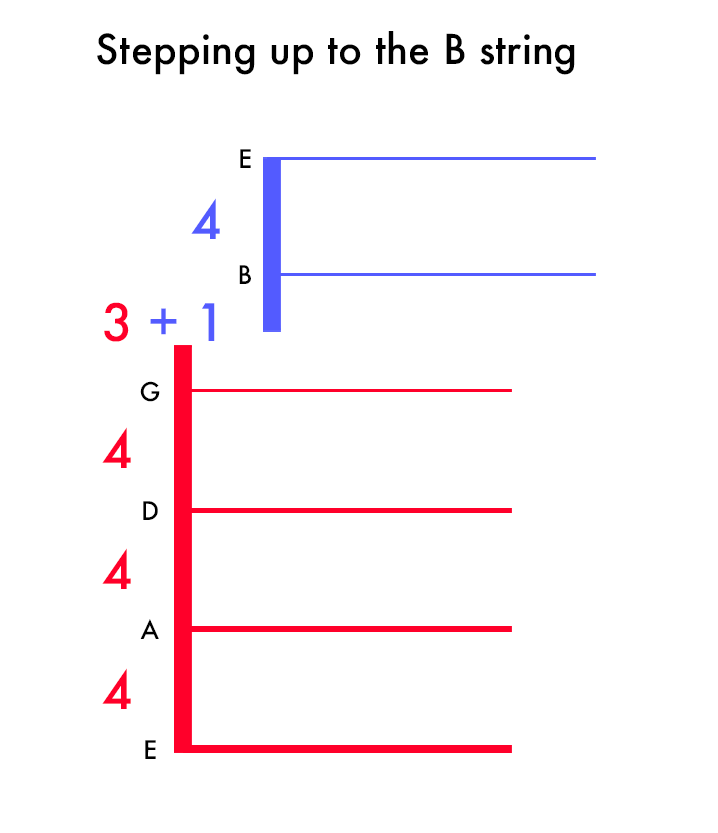

Fig. 2: We compensate for the third interval by shifting our patterns up one fret when we reach the B string.

Here’s a good analogy to help us understand what’s going on:

If you go for a walk around the block, you might be walking in a square. Let’s say your neighbourhood is pretty flat so it’s an easy walk. But perhaps you’re visiting a friend and decide to go for a walk around their neighbourhood. Their suburb is full of hills. You’ll still be walking around the block in the shape of a square; the shape is the same. However, the experience of walking will be quite different. You have to go up the hill and then down again. The shape doesn’t change, but the landscape (and the experience of walking over it) is different.

This is what it’s like when we play a scale using the B string. The shape is the same but the experience of moving through the terrain is different.

Here’s how we deal with the changing landscape of the B string:

The B string is only three notes away from the G string (rather than four), so we have to compensate by ‘adding’ a fret to our scale shapes when they cross over onto the B string.

Another way to think about it is like a platform. When you get to the B string, you have to step up (by one fret) onto the platform. Once you’re up there you stay in that position for the rest of the strings (the high E). If you want to step back off the platform, you have to go back down by one fret.

It might take a second to get used to what it’s like to move your scale shapes onto the B string. But it means that you only have to learn one shape for each scale. It’s the same shape; you’re simply adjusting it as the landscape changes.

A guitarist who has learned all the notes on the fretboard: Can more effectively learn scales and chords; Has a better understanding of keys, intervals, and scale degrees; Is able to more easily memorise songs; Has a greater capacity to understand music theory; Is more effectively able to develop their aural skills; Gets ‘lost’ far less frequently when they are improvising on the guitar.